Why the United Nations Has Become Ineffective — and Why a New Board of Peace Is Needed for the 21st Century

For nearly eight decades, the United Nations has been positioned as the central global body responsible for maintaining international peace and security. Established in the aftermath of World War II, the UN was designed to prevent another global catastrophe through collective security, diplomacy, and cooperation.

Yet today, amid escalating wars, proxy conflicts, humanitarian catastrophes, and geopolitical paralysis, the UN is widely viewed as ineffective, compromised, and structurally incapable of resolving modern conflicts. This reality has driven renewed calls for an alternative framework — one designed for speed, accountability, and outcomes rather than procedure and politics. The proposed Board of Peace represents such an approach.

This article examines why the UN has failed, how corruption and structural weaknesses undermined trust, and why a new peace architecture is increasingly necessary.

The Structural Failure of the United Nations

A System Designed for a Different Era

The UN’s core security mechanism — the Security Council — reflects the geopolitical realities of 1945, not 2026. Five permanent members retain veto power, allowing any one of them to block action regardless of humanitarian urgency or global consensus.

As a result:

Major conflicts involving powerful states or their allies often stall indefinitely

Resolutions are diluted, symbolic, or never enforced

The UN becomes reactive rather than preventative

This structure has produced paralysis in precisely the conflicts where decisive action matters most.

A History of Corruption and Institutional Breakdown

Documented Corruption Scandals

The UN’s credibility has been repeatedly damaged by major scandals that exposed systemic governance failures, including:

The Oil-for-Food Program (Iraq), which revealed widespread mismanagement, kickbacks, and lack of oversight

Persistent cases of fraud, abuse, and financial misconduct across multiple UN agencies

Repeated failures to prevent or respond swiftly to sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeeping forces

These incidents share a common thread: internal investigations, limited accountability, and minimal consequences, reinforcing the perception that the institution lacks effective self-policing mechanisms.

Peacekeeping Without Peace

UN peacekeeping missions often suffer from:

Limited mandates that prevent intervention

Rules of engagement that prioritize neutrality over civilian protection

Chronic funding shortfalls that reduce troop levels and operational capacity

Historical failures — including the inability to prevent mass atrocities in multiple regions — have left a lasting stain on the UN’s reputation. In many cases, peacekeeping forces were present but powerless.

The Trust Deficit

Globally, the UN faces a growing trust gap driven by:

Perceived double standards in enforcement

Political capture by powerful states

Excessive bureaucracy with limited results

Inability to adapt to asymmetric warfare, non-state actors, and hybrid conflicts

For many governments and populations, the UN is no longer seen as a credible guarantor of peace — but as a forum for statements rather than solutions.

Why a New Board of Peace Is Needed

Designed for Modern Conflict

The proposed Board of Peace is not a replacement of diplomacy, but a restructuring of how peace is pursued. Its design reflects lessons learned from decades of UN failure.

Key structural advantages include:

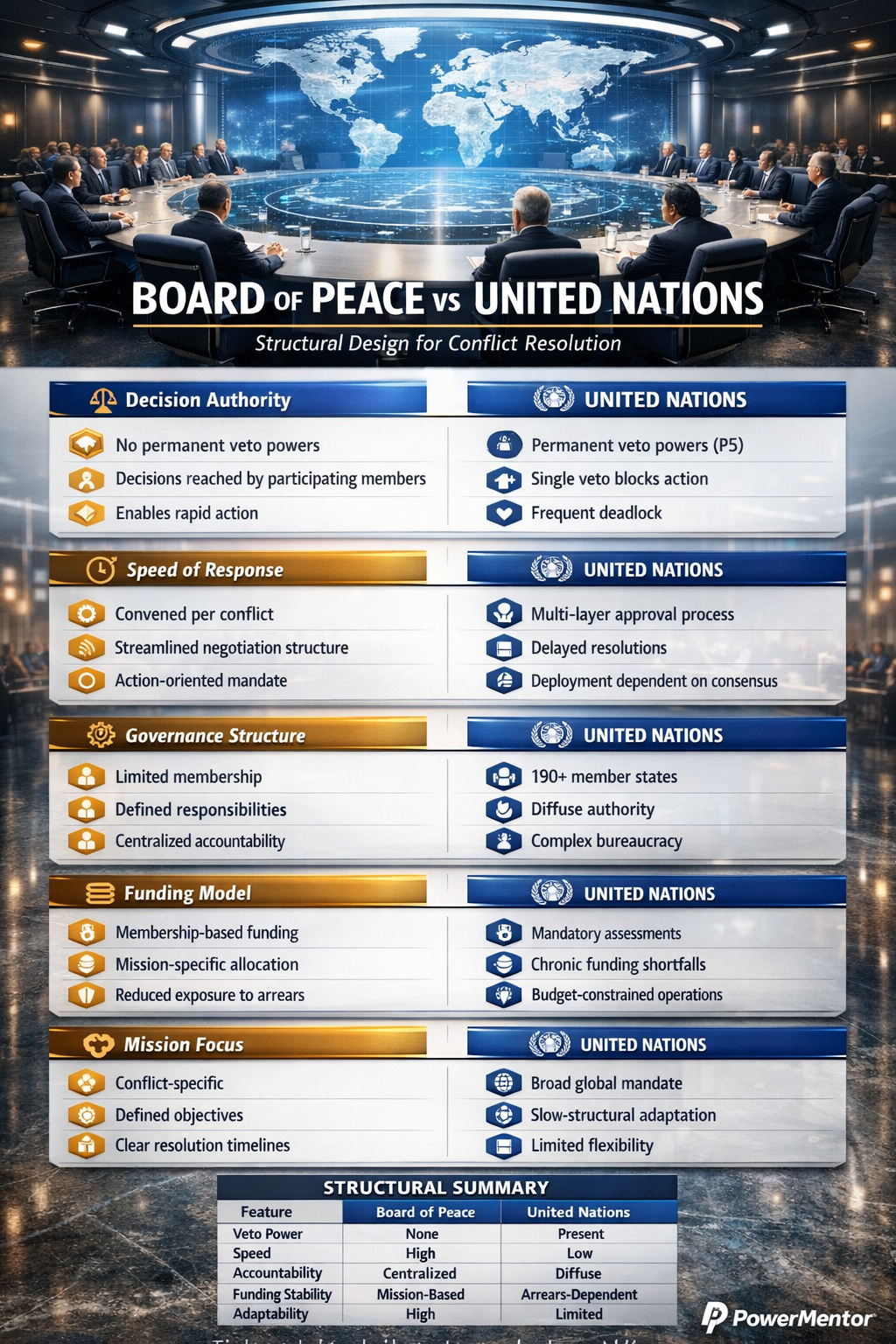

1. No Permanent Veto Powers

Decisions are not hostage to a single state

Action is determined by participating members

Deadlock is structurally minimized

2. Speed and Flexibility

Convened specifically for active conflicts

Streamlined governance reduces procedural delay

Negotiation and mediation are prioritized over declarations

3. Clear Accountability

Limited membership with defined responsibilities

Centralized leadership enables ownership of outcomes

Success and failure are measurable

4. Sustainable Funding Model

Membership-based contributions

Mission-specific funding

Reduced exposure to arrears and budget paralysis

5. Outcome-Oriented Mandates

Defined objectives and timelines

Focus on resolution rather than indefinite presence

Designed to adapt as conflicts evolve

A 21st-Century Peace Architecture

The Board of Peace represents a shift from:

Process to results

Symbolism to enforcement

Bureaucracy to accountability

It acknowledges a reality the UN has struggled to confront: modern conflicts require rapid coordination, credible leverage, and decisive mediation, not endless debate.

Representatives of several countries signed onto the charter forming the Board of Peace at Thursday’s ceremony: Argentina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Hungary, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Mongolia, Pakistan, Paraguay, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Uzbekistan. Additional countries that have accepted Trump’s invitation to join the Board of Peace are: Albania, Bahrain, Belarus, Egypt, Israel, Kuwait, Morocco and Vietnam.

As detailed in its charter, membership in the Board of Peace lasts for a three-year term and is subject to renewal by Trump. The charter clarifies that “the three-year membership term shall not apply to Member States that contribute more than USD $1,000,000,000 in cash funds to the Board of Peace within the first year of the Charter’s entry into force.” While the charter's provisions on three-year terms for Board of Peace membership suggest the international body will be around for a while, additional language in the document indicates it could dissolve in the near future. “The Board of Peace shall dissolve at such time as the Chairman considers necessary or appropriate, or at the end of every odd-number calendar year, unless renewed by the Chairman no later than November 21 of such odd-number calendar year,” the charter states.

There is growing concern among observers, institutions, and allied governments regarding the increasing concentration of global influence and decision-making authority associated with Donald Trump, particularly through the creation and leadership of new international mechanisms operating outside established multilateral frameworks.

While strong leadership and decisive action are often valued during periods of global instability, the accumulation of diplomatic, financial, and strategic authority within a single executive figure raises fundamental questions of accountability, transparency, and checks and balances—especially when such authority extends beyond national borders. Most recognize the UN is no longer effective, and often most of the time is part of the problem in enabling conflicts rather than solving them.

Key concerns include:

Unclear lines of accountability: New global initiatives led outside traditional treaty-based institutions lack clearly defined oversight mechanisms, raising questions about who ultimately holds decision-makers accountable for outcomes, failures, or unintended consequences.

Erosion of multilateral governance norms: When parallel structures supplant existing international institutions rather than reform them, there is a risk of weakening long-standing norms designed to distribute power, prevent unilateral dominance, and ensure collective responsibility.

Concentration of influence: The centralization of diplomatic authority, funding leverage, and agenda-setting power in one office or individual may reduce institutional restraint and increase dependence on personal discretion rather than durable governance systems.

Precedent for future leaders: The normalization of personalized global authority creates a precedent that may be adopted by future leaders with fewer safeguards, weaker commitments to transparency, or less respect for democratic norms.

Global legitimacy and trust: International cooperation relies on trust not only in outcomes, but in processes. When decision-making structures lack shared governance, legitimacy can be questioned even when intentions are stated as constructive.

This concern is not rooted in opposition to peace initiatives or reform, but in the principle that sustainable global leadership must be accountable, institutionalized, and constrained by clear rules. History demonstrates that peace and stability are best preserved when power is balanced, oversight is explicit, and no single actor—regardless of intent—operates without meaningful checks.

The long-term effectiveness of any new global framework will depend not only on speed or authority, but on who oversees it, how decisions are reviewed, and where responsibility ultimately rests.

Conclusion

The United Nations was built for a post–World War II world that no longer exists. Its structures, incentives, and power dynamics have left it unable to fulfill its founding promise in the face of modern geopolitical realities.

A new Board of Peace offers an alternative — not rooted in nostalgia or size, but in effectiveness, accountability, and adaptability. Whether it ultimately succeeds will depend on implementation, integrity, and global participation. But its very emergence underscores a hard truth:

Peace in the 21st century requires new tools — because the old ones no longer work.

References

Alaaeldin, M., & Cornwell, A. (2026, January 22). What is Trump’s “Board of Peace” and who has joined so far? Reuters.

Anna, C., & Boak, J. (2026, January 18). $1 billion gets a permanent seat on Trump’s Board of Peace for Gaza, as India and others invited. The Washington Post (Associated Press story).

Chesterman, S. (2026). Untied Nations? Saving the UN Security Council. European Journal of International Law.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2006, May 12). The impact of the UN Oil-for-Food scandal. Council on Foreign Relations.

Frankel, J. (2026, January 21). A look at Trump’s Board of Peace and who has been invited. The Washington Post (Associated Press story).

Guterres, A. (2025, December 1). UN chief warns unpaid dues near $1.6 billion, as budget cuts deepen. United Nations Office at Geneva.

International Service for Human Rights. (2025, October 21). UN liquidity crisis: Analysis of contributions paid by UN member states by date of payment (2019–2025).

Moraa, A. (2024, April 5). Report of the Secretary-General on special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse. SecurityWomen (posting of the UN report reference).

Pew Research Center. (2025, July 31). How the United Nations is funded, and who pays the most. Pew Research Center.

Reuters. (2025, October 8). UN to slash a quarter of peacekeepers globally over lack of cash. Reuters.

Reuters. (2026, January 18). Trump’s Gaza peace board charter seeks $1 billion for extended membership, document shows. Reuters.

Reuters. (2026, January 21). Italy won’t take part in Trump’s “Board of Peace”, Corriere says. Reuters.

Security Council Report. (2025, November 17). UN peacekeeping operations: Closed consultations. Security Council Report.

United Nations. (2005, September 7). Oil-for-Food Programme: Security Council briefing/coverage. UN Meetings Coverage & Press Releases.

United Nations. (2025, October 9). With Member States still owing $1.87 billion in mandatory contributions, Organization’s cash position has not improved, budget chief tells Fifth Committee. UN Press Release (GAAB).

United Nations. (2025, December 15). Paralysis, shrinking aid, outdated methods highlight need for… UN Meetings Coverage & Press Releases.

United Nations. (2024). Annual report of the Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (2024). United Nations.

United Nations. (2023). Annual report of the Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (2023). United Nations.

UK House of Commons Library. (2025, October 30). UN at 80: Funding challenges at the United Nations (Research Briefing CBP-10379).

Washington Post Staff. (2026, January 22). Trump’s Board of Peace has divided the globe. Here are the participants. The Washington Post.