The Karens of Burmah and the Pattern of Exile and Restoration

A Deep Reading of Dr. Francis Mason’s 1834 Argument

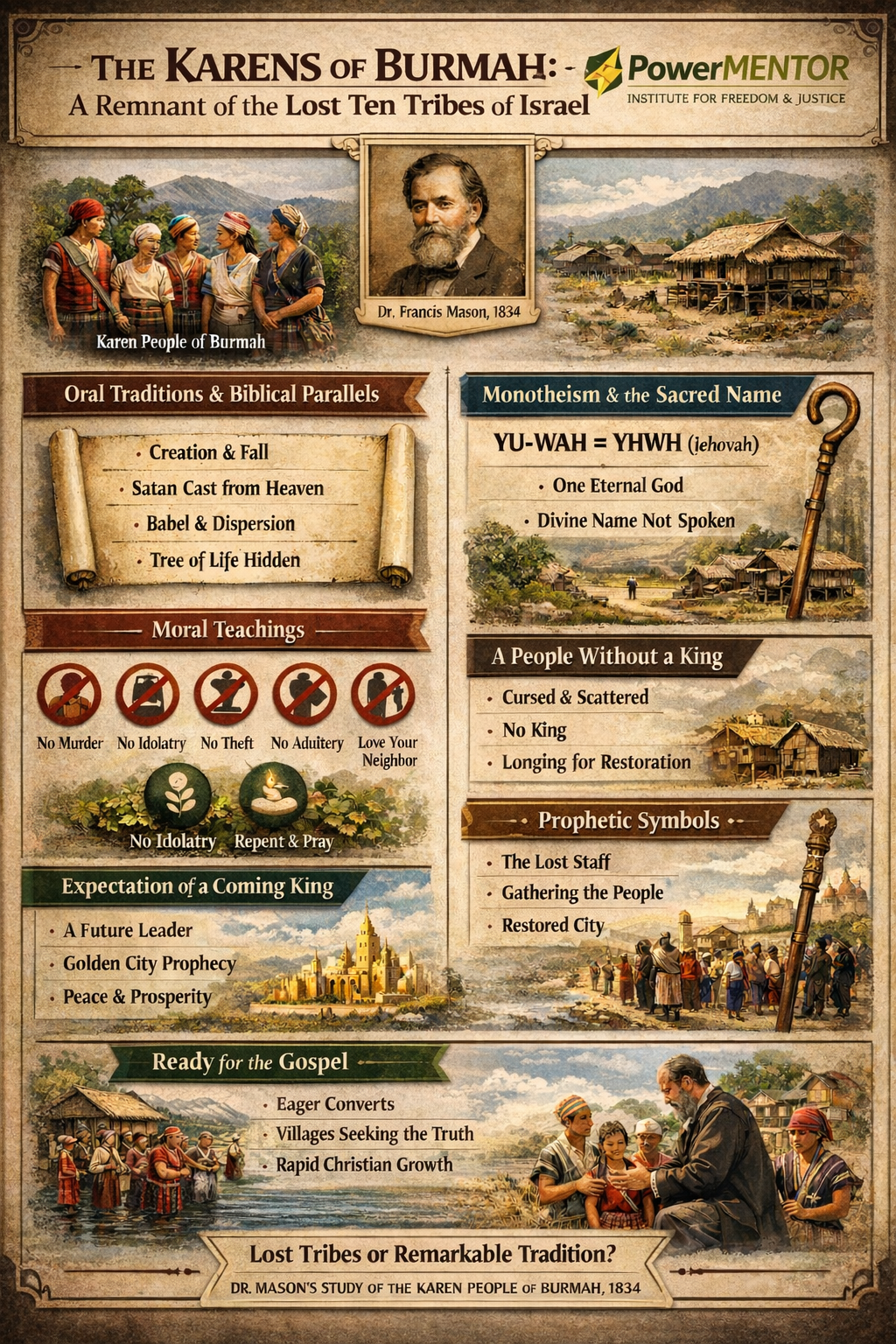

In his 1834 paper The Karens of Burmah a Remnant of the Ten Tribes of Israel, Dr. Francis Mason presents a carefully constructed argument grounded not in genetics or archaeology, but in theological pattern, prophetic correspondence, and preserved religious memory. Mason’s claim is not merely that the Karen people resemble ancient Israel in isolated ways, but that their collective self-understanding follows the same covenantal arc described in the Hebrew Scriptures.

At the heart of Mason’s thesis is a single organizing idea:

the Karens understand themselves as a people once favored by God, later rejected because of disobedience, now living in affliction and dispersion, and awaiting divine restoration. This, Mason argues, is precisely how Scripture describes the fate of the Ten Lost Tribes.

Oral Tradition as Covenant Memory

Mason places extraordinary emphasis on Karen oral tradition, describing it as unparalleled among so-called “uncivilized nations.” These traditions are not casual folklore but structured moral and theological instruction, often introduced with the repeated address: “O children and grandchildren!”

Two features stand out:

Continuity across generations – The traditions are explicitly framed as ancestral instruction.

Liturgical preservation – Many traditions are preserved in verse and sung at funerals, embedding theology into rites of memory and mourning.

Mason notes that these poems exhibit the cadence, repetition, and moral gravity characteristic of Hebrew sacred poetry. In his view, this is not accidental: it is the residue of a covenant people who lost their written law but preserved its substance in song.

The Eternal God and the Withheld Name

Central to Mason’s argument is Karen monotheism. The Karens worship a single, eternal, uncreated God who existed “in the beginning of the world” and whose existence is not measured by time or succession. This God is morally perfect, omniscient, and sovereign over history.

Crucially, the Karens possess a proper name for God—Yu-wah—yet refuse to pronounce it casually. Mason draws attention to the Karen belief that invoking God’s proper name improperly causes Him to withdraw rather than draw near.

This dual reality—a known divine name coupled with a prohibition against its use—is foundational to Mason’s comparison. It mirrors the Hebrew reverence for the divine name, in which God is known but not spoken, present yet withdrawn. For Mason, this is not a superficial similarity but a shared theological instinct rooted in covenant reverence.

Scriptural History Without Scripture

One of the most striking aspects of Mason’s paper is the sheer number of Old Testament narratives preserved in Karen tradition—without access to the Bible.

These include:

Creation and the formation of woman from man

A deceiving adversary who was once righteous but fell through disobedience

The Fall, resulting in death entering the world

A “tree of death” and a hidden “tree of life”

Moral corruption inherited through generations

The dispersion of humanity through the division of language

Mason does not argue that the Karens possess Scripture; he argues something more precise: they possess memory of Scripture events without Scripture itself. In his framework, this is exactly what one would expect of a people cut off from revelation yet not erased from God’s purposes.

Moral Law Without Ritual Law

A defining feature of the Karen tradition, in Mason’s view, is the presence of biblical morality without biblical ritual.

The Karens condemn:

Murder

Theft

Adultery

Lying

Covetousness

Idolatry

They affirm:

Repentance

Prayer

Divine judgment

Reward and punishment after death

Love of neighbor

Honor toward parents

At the same time, they lack:

Sacrificial systems

Circumcision

Priestly institutions

Temples

Feast days

Mason explicitly links this condition to prophetic descriptions in Hosea, where Israel is said to exist “many days without a king, without sacrifice, without ephod.” In other words, moral identity remains intact while ceremonial identity disappears—a hallmark of exile.

Hosea 5:15 and the Theology of Divine Withdrawal

This is where Mason’s footnote becomes essential.

Hosea 5:15 states that God will withdraw “to my place” until the people acknowledge their offense and seek His face, particularly in affliction. Mason sees this verse as a theological key that unlocks Karen self-understanding.

The Karens repeatedly state:

God once loved them above all others

They disobeyed His commands

God “went away”

They are cursed, afflicted, and without books

God will return and show mercy again

For Mason, this is not metaphorical similarity; it is the same covenant logic. God does not annihilate His people—He withdraws. Affliction is not abandonment but discipline. Suffering is not the end of the relationship but the mechanism that leads to repentance and restoration.

Isaiah 64:7–9 and the Cry of the Fatherless People

Mason pairs Hosea with Isaiah 64:7–9, where the people lament that God has hidden His face and allowed them to be consumed by their sins—yet still call Him “our Father.”

This tension—divine distance without divine rejection—is central to Mason’s reading of the Karen condition. The Karens believe God is absent but not gone, silent but not dead, withdrawn but not severed.

They wait.

A People Without a King

Mason highlights that the Karens explicitly state: “Because the Karens transgressed the commands of God, they have no king.” He links this to Hosea’s declaration: “We have no king, because we feared not the Lord.”

Statelessness is not viewed as political failure but as theological consequence. The absence of a king is proof of covenant breach, not ethnic insignificance.

Expectation of Restoration and the Coming King

Despite affliction, the Karens are not fatalistic. They anticipate:

A coming king

A restored city (silver city, golden palace, new city)

Universal peace

Social equality

Harmony in creation

The end of oppression

Importantly, this expected king is not divine, nor is he a redeemer from sin. He is a leader raised up by God to restore order, prosperity, and justice—precisely the expectation held by Israel prior to and during exile.

Their prophetic hymns describe staffs, gathering, cities springing forth, and divine timing—symbols Mason interprets as encoded restoration theology.

Readiness for Restoration

Mason concludes with what he views as experiential confirmation: the unprecedented readiness of the Karen people to receive the Gospel. He interprets this not as coincidence but as fulfillment—the moment when a long-withdrawn God begins to return to a people who have been waiting for generations.

Conclusion: Mason’s Argument on Its Own Terms

Read properly, Mason’s paper is not a claim about race; it is a claim about covenant memory.

He is saying this:

The Karen people remember themselves the way Israel remembers itself in exile.

They explain suffering the way Scripture explains exile.

They hope the way Scripture says exiles hope.

Whether one agrees with his ultimate conclusion or not, Mason’s work stands as a profound theological ethnography—an attempt to read a people’s story through the deep grammar of Scripture rather than surface resemblance.

References

Mason, F. (1834). The Karens of Burmah a remnant of the Ten Tribes of Israel. The Calcutta Christian Observer. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/calcuttachristia03unse/page/210

The Holy Bible, King James Version. (n.d.). Hosea 5:15; Hosea 3:4; Isaiah 64:7–9.

Crossing, M. (2024). Karen of Burmah – Remnant of the Ten Tribes of Israel. Lost Tribes Institute. Retrieved from https://independent.academia.edu/MargotCROSSING