Shunda Park: When Karen Land Becomes a Factory for Global Fraud — and Why Whistleblowers Like Nerdah Bo Mya Keep Getting Attacked

In December 2025, the world got a rare look behind the razor wire.

Shunda Park — a purpose-built “office park” in Min Let Pan, Karen State — wasn’t designed to create jobs, grow the local economy, or serve a community. It was engineered to industrialize deception: rows of computers, staged “executive” rooms for video calls, scripts and notebooks on how to manipulate victims, and a culture that celebrated theft like a sales milestone. Reports describe thousands of workers from dozens of countries, some trafficked or coerced, pushed through relentless quotas and brutal punishment systems.

And here’s the part too many people miss: Karen communities didn’t build this. Karen communities are living inside the blast radius—caught between war, displacement, and transnational crime networks that use conflict zones as cover.

A crime economy that thrives on chaos

Across the Thai–Myanmar borderlands, scam compounds have grown into one of the most lucrative criminal ecosystems on earth, mixing crypto fraud, romance scams (“pig butchering”), trafficking, forced labor, money laundering, and militia protection arrangements. Reuters has documented how people are recruited via fake job offers and then forced to scam strangers under threat of violence.

Meanwhile, international pressure spikes, headlines flare, and then… the machine adapts. Workers get moved. Evidence gets burned. New compounds go up a few miles away.

That is why Shunda Park matters: not because it’s “the” scam center, but because it’s a window into how the entire scam economy operates like a franchised industry inside a war zone.

The Karen dilemma: “Don’t make our land the world’s scam capital”

Local resistance forces have publicly expressed frustration that Karen territory is being branded globally as a criminal hub. That anger is real—and valid—because the scam economy doesn’t just steal money from victims overseas. It poisons legitimacy locally, fuels corruption, funds armed actors, and turns civilians into collateral damage when fighting escalates around these compounds.

At the same time, the scam economy survives precisely because it can buy protection, electricity, internet, land leases, and silence—often through layered relationships involving militias, business entities, and political actors.

The uncomfortable political layer: allegations, denials, and the fight for credibility

This is where the story stops being a “cybercrime” article and becomes a Karen political crisis.

What investigative reporting has alleged

An Irrawaddy investigation reported that contracts and documentation tied to the KNU (Karen National Union) were connected to projects in the same border “new city” ecosystem widely associated with scamming, trafficking, and abuse—while also detailing how these zones operated alongside militia power.

What the KNU has said in response

The KNU has strongly denied involvement in these “new city” projects and scam-linked criminality.

So you have a reality that looks like this:

Serious reporting and civil society investigations raising documentation-based concerns,

while official KNU statements reject the allegations and frame some claims as politically motivated or junta propaganda.

That tension isn’t just “politics.” It’s the heart of whether Karen governance can credibly claim it is building a future free of both dictatorship and criminal capture.

Nerdah Bo Mya: the whistleblower narrative vs. the official narrative

General Saw Nerdah Mya (often referred to as Nerdah Bo Mya) sits right in the middle of this storm.

What’s widely documented about the split

Multiple outlets describe Nerdah as a former KNU/KNDO figure who later founded the KTLA after being dismissed/expelled by the KNU amid accusations and internal disciplinary conflict involving a battle his commanders were involved in with Burmese soldiers dressed in civilian clothes that died in the battle.

KNDO asserts the following:

In the Wah Lay incident, the KNU has been cited as asserting that those killed were civilians—a claim that has also been used to attack Nerdah Bo Mya and the KNDO politically. The KNDO, however, rejects that characterization and says it operates consistent with international human rights standards and exists to defend civilians, noting that all women and children detained in Wah Lay were released unharmed.

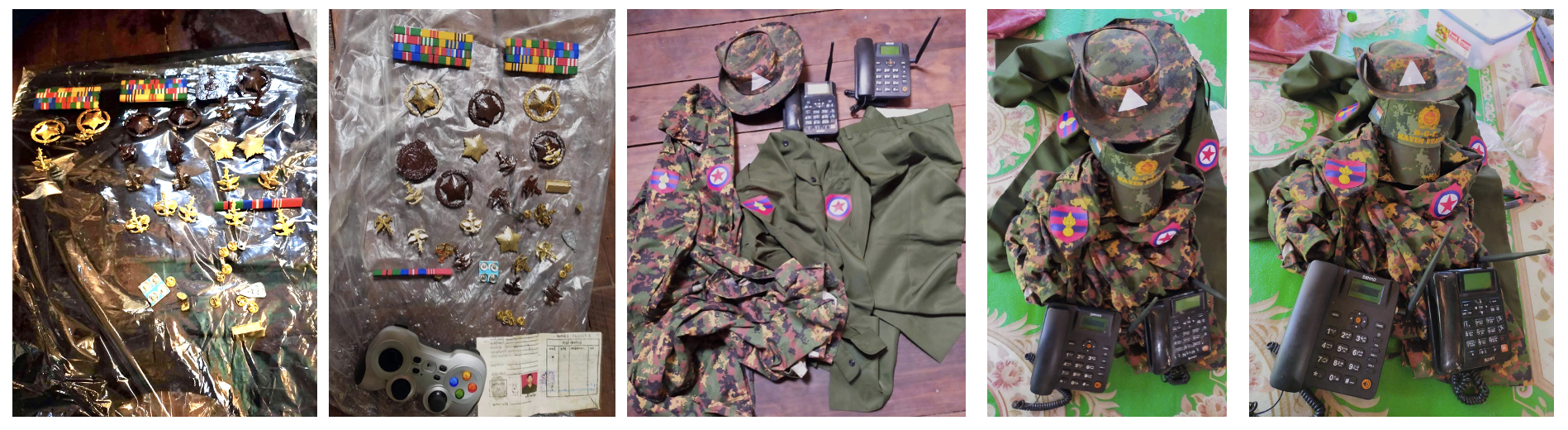

According to the KNDO’s account, the deceased were Tatmadaw military personnel, not civilians, and the deaths occurred during a mass breakout attempt amid an artillery bombardment conducted by their own side—with the KNDO alleging some Tatmadaw soldiers were killed by their own artillery. The KNDO also reports that several KNDO soldiers were wounded during the incident. Supporters further point to military uniforms found and photographed as evidence they say directly contradicts the claim that those killed were civilians, and they emphasize that Nerdah was not present when the clash occurred, yet the incident continues to be used to justify targeting him.

Why supporters see him as a threat to the “old system”

Supporters of Nerdah argue something different: that he has repeatedly exposed corruption and criminal entanglements—including scam-center economics—and that doing so made him a target. In that view, the attacks on him are not just about discipline or misconduct, but about shutting down exposure.

Here’s what we know based on public documentation:

The KNU has shown a pattern of moving against Nerdah when he publicly escalated issues into the open (including public postings tied to internal investigations), framing it as refusal to cooperate and disregard for organizational process.

Separately, there is a documented public dispute between KNU leadership and Nerdah/KTLA over legitimacy, authority, and claims of representing Karen governance.

And in the broader scam-center ecosystem, credible reporting and watchdog investigations continue to raise questions about who profits, who protects, and who looks away—questions that naturally create enemies for anyone pushing sunlight into the system.

Bottom line: Whether you see Nerdah as reformist, rival, or renegade—his presence forces one question that Karen politics can’t dodge anymore:

Will Karen leadership confront the scam economy as an enemy of the people… or treat it as a problem to manage, deny, and outlast?

Why Shunda Park is a warning, not a one-off

What happened at Shunda Park shows how fast criminal infrastructure can “metastasize” when four conditions exist:

Territory contested by war

Cross-border access (Thailand as transit and logistics corridor)

A workforce pipeline built on deception and trafficking

Protection and profit-sharing structures that blur politics, militia control, and business deals

And that’s why “raids” and “crackdowns” so often feel cosmetic: the scam industry doesn’t need permanence. It needs mobility.

What real accountability could look like

If Karen society is serious about stopping this, the fight can’t be only military. It has to be governance:

Independent investigations that are not controlled by any one armed actor

Transparency on land leases, business partners, utilities, and taxes/fees in border zones

Protection for whistleblowers and journalists (because fear is the scam economy’s best friend)

International coordination that treats scam compounds as a hybrid threat: cybercrime + trafficking + organized crime + conflict finance

Because without that? The world will keep reading stories about Karen State as the setting for global fraud—and Karen civilians will keep paying the price for crimes they didn’t create.

References

Beech, H. (2026, January 13). At this office park, scamming the world was the business. The New York Times.

Department of Justice, U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia. (2025, December 2). Scam Center Strike Force announces seizure of fake cryptocurrency investment domain used to victimize Americans. https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/pr/scam-center-strike-force-announces-seizure-fake-cryptocurrency-investment-domain-used

Department of Justice, U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia. (2025, December 18). Scam Center Strike Force. https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/scam-center-strike-force

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2025, April 23). FBI releases annual Internet Crime Report. https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/fbi-releases-annual-internet-crime-report

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Internet Crime Complaint Center. (2024). 2024 IC3 annual report. https://www.ic3.gov/AnnualReport/Reports/2024_IC3Report.pdf

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. (2025, May). Compound crime: Cyber scam operations in Southeast Asia. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/GI-TOC-Compound-crime-Cyber-scam-operations-in-Southeast-Asia-May-2025.pdf

Reuters. (2025, November 21). Global pressure forces Myanmar junta to crack down on scam centres, sources say. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/global-pressure-forces-myanmar-junta-crack-down-scam-centres-sources-say-2025-11-21/

Reuters. (2025, April 21). Billion-dollar cyberscam industry spreading globally, UN says. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/cancer-billion-dollar-cyberscam-industry-spreading-globally-un-2025-04-21/

U.S. Department of State, Office of the Spokesperson. (2025, September 8). Imposing sanctions on online scam centers in Southeast Asia. https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/09/imposing-sanctions-on-online-scam-centers-in-southeast-asia

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2025, September 8). Treasury sanctions Southeast Asian networks targeting Americans with cyber scams. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0237

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2025, October 14). U.S. and U.K. take largest action ever targeting cyber scam operations in Southeast Asia. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0278

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2025, November 12). Treasury sanctions Burma armed group and companies involved in cyber scams targeting Americans. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0312

U.S. Secret Service. (2025, November 12). New Scam Center Strike Force battles Southeast Asian crypto investment scams. https://www.secretservice.gov/newsroom/releases/2025/11/new-scam-center-strike-force-battles-southeast-asian-crypto-investment

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2024). Transnational organized crime and the convergence of cyber-enabled fraud, underground banking and technological innovation in Southeast Asia: A shifting threat landscape. https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2024/TOC_Convergence_Report_2024.pdf

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2025). Inflection point: Global implications of scam centres, underground banking and illicit online marketplaces in Southeast Asia. https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2025/Inflection_Point_2025.pdf

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). (2024, July). Crushing scam farms, Southeast Asia’s “criminal service providers”. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/frontpage/2024/July/crushing-scam-farms--southeast-asias-criminal-service-providers.html

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). (2025, April 21). Cyberfraud in the Mekong reaches inflection point, UNODC reveals. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/frontpage/2025/April/cyberfraud-in-the-mekong-reaches-inflection-point--unodc-reveals.html

XCEPT Research. (2024). Scam city: How the coup brought Shwe Kokko back to life. https://www.xcept-research.org/publication/scam-city-how-the-coup-brought-shwe-kokko-back-to-life/